In the open studio of a renovated 36,000-square-foot factory in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, a series of Shima Seiki automated knitting machines emit quick, whirring sounds. Around the machines, automated guided vehicles transport materials including spools of yarn in a Crayola box of colors, while robot arms fuss with uppers and outsoles rolling down the conveyor lines. Desks are buzzing with teams crowding over computers animatedly discussing design plans. This is the headquarters of KX Lab, a brand-new manufacturing facility making knit sneakers, through mostly automated techniques, in the heart of one of America’s most important urban sprawls.

These days, when you look at the bottom of your sneakers, rarely do they say “made in the USA.” While the US is the leading importer of footwear in the world (it received some 2.4 billion pairs in 2021), this is not the country where shoes are made, generally speaking. In 2021, China, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia accounted for nearly 75% of the world’s footwear production. (China is far-and-away number one with over 12 billion pairs; India, number two, produced 2.6 billion last year.) The reason why is obvious: It’s cheaper to get shoes made in Asia than it would be to get them made nearly anywhere else, but especially stateside.

There is shoe production happening in the US, but on a much smaller scale. Last year, New Balance opened its fifth domestic factory, an 80,000-square-foot facility in Massachusetts. But a price comparison on New Balance’s website shows that a pair of Made in the USA sneakers start at $184.99, while sneakers whose provenance is unknown (New Balance still sources parts from overseas for many of its shoes), however, could start as low as $64.99 a pair. While many factors influence price, domestic shoe manufacturing is unequivocally much more expensive.

So when Joshua Katz opened KX Lab, his focus wasn’t on cost-saving—it was on sustainability and creative collaboration. Katz says that the lab is designed to bring the “product-creation engine” much closer to both the people who are creating and the consumers who buy the finished product. “If you can work with the factory down the street, you can produce smaller runs, be closer to sampling and development, and bring products to market on a smaller scale,” he explains, adding that this allows for the lowering of carbon emissions that would otherwise come from global transport. But for Katz, there’s also the critical opportunity for brands to be much more involved with the creation process and perhaps feel inspired to take more risks.

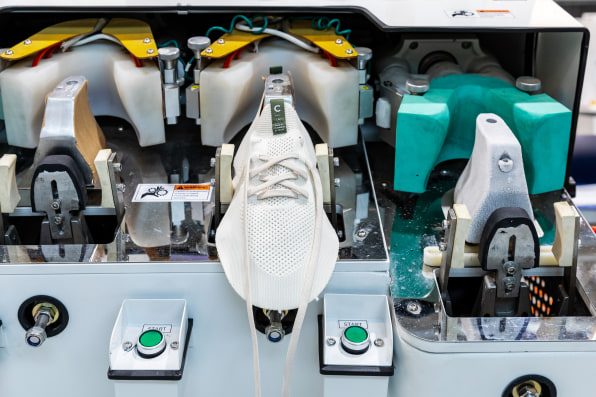

While automated knit sneaker production has been thriving in Asia for years, it remains a largely new fabrication method in the West. And to educate brands into getting on board, KX Lab was built “like a prototype facility in the sense that here we have the opportunity to experiment, learn, and improve,” Katz says, adding that the lab is constantly evolving with the goal of identifying how knit fabrication can become more valuable to the American design industry. The Shima Seiki automated knitting machines—the standard bearer in knit footwear—can churn out whole-knit sneaker uppers in 25 minutes. Upper designs are fed into a program, and the Shima Seiki knits it whole. Laser cutting machines are used to make reinforcement components. The goal is to minimize waste and physical labor.

Late last year, LA-based Clae, known since 2001 for minimalist sneakers in classic silhouettes, unveiled its first made-in-the-USA style in partnership with KX Lab. The Louie, a lifestyle sneaker that resembles a running shoe (though not designed for a specific athletic activity), features Clae’s signature sleek aesthetic plus more technical elements like a variety of knitting styles: tight where you want it like a snug collar that comfortably wraps around the ankle, looser where you want more breathability.

The technology involved also led to some dropped jaws, especially when the Clae team saw robotic arms (similar to what car manufacturers would use) applying the glue that would connect the printed uppers with the soles. Clae has also long been committed to sustainability, ensuring its factories in Vietnam pay fair wage, launching cactus-leather sneakers in partnership with tanneries in Mexico. The team appreciates how knit manufacturing uses laser-cutting technology to minimize waste; plus, a single-piece print-out requires no adhesive.

“We priced this shoe lower than we normally would, but that was due to the simplicity of the design and how that translates into the perception of cost and value,” Clae CEO Jim Bartholet admits. “We also wanted it to be accessible.” A limited-edition run that wasn’t necessarily cost-effective led the brand to forgo wholesaling the Louie—it’s exclusively available for purchase through Clae.

For its foray into domestic production, Clae adopted a largely experimental mix-and-match approach when it came to sourcing because of the up-front cost. The entire knit upper was created in KX Lab; while the outsoles, laces, and insoles were made by existing factory partnerships in Vietnam. But looking at Clae’s inventory of sneakers, the Louie slots in comparably on the top end of their retail range at $180 per pair.

But Bartholet says that because KX Lab’s automated manufacturing process is less labor-intensive, a bigger order could help tip the cost more favorably. And even still, the benefits of locally producing a shoe outweigh added expense. Clae’s senior designer Ji-San Lee agrees that the proximity was a game-changer. Clae shoes are typically produced abroad (its last knit low-tops were made in Vietnam), but a factory located an hour from their HQ? That makes a massive difference. “Often with design these days, it’s very easy to just send off your work and hope it gets interpreted correctly by the developer or pattern maker,” Lee adds. “So it was a breath of fresh air to be able to sit down with other creatives, and find work-arounds or solutions anytime we would hit a snag in the design process.”

Just like how diners are favoring more sustainability in food, Katz also knows that consumers are eager to understand how their stuff is made. “There’s already been a transition from the opaque black box of how and where things are made to a more transparent production process,” he says. “And that can be as important as the materials themselves.” The brands making shoes at KX Labs are hoping to capitalize on that growing interest.

KX Lab has only been around for less than a year, and most of what it’s produced has been sneakers. But Katz is convinced that there’s much more that can be done. The KX team is researching how automated knitting can be implemented in the worlds of apparel, home goods, and cars. Katz says he’s encouraging them to push the boundaries in how the existing technology can be used, like thermoforming fuse yarns, and exploring how it can be combined with other production techniques like 3D printing.

“Los Angeles is one of the hardest places to manufacture products,” he says. “There are stringent environmental regulations; the cost of living is high so the cost of labor is high. But we said if we can do it here, we can probably do it anywhere.”

BY CHADNER NAVARRO